“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is necessity; that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.” John Muir

“In many people’s minds, mountains represent all that is good in nature, they are the antithesis of the city… Whilst most of us spend nearly all our lives in cities, it is not a complete existence... we are increasingly drawn towards the mountains to escape and to experience nature. They offer solitude and stand lonely among the last bastions of wildness on the earth.” (Larry Price, 1981)

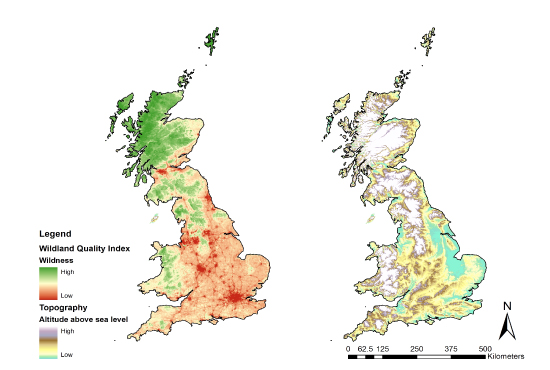

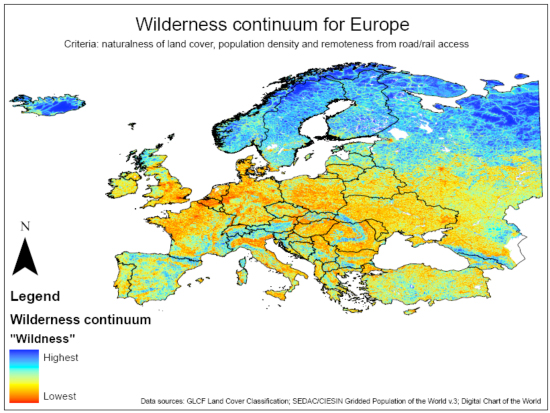

These two quotes from John Muir and Larry Price serve to underline the importance of mountains in the human psyche as wild places. Mountains by their very nature appear wild; they are rugged and often remote and inaccessible, they are dynamic physical environments that attract extreme weather conditions and give rise to extreme events such as avalanches and landslides, they are generally less hospitable than their lowland counterparts, creating more difficult conditions for human habitation and agriculture, and they often represent, as Price acknowledges, the last bastions of wild nature in an otherwise human dominated world. It is hardly surprising then, that with many of our lowland wetland, woodland, grassland and coastal environments altered by thousands of years of human activity, that there is a strong correlation between many national maps of wilderness and the underlying topography. A quick visual comparison between the maps of wilderness quality and altitude for Britain confirms this pattern (see Figure 1) while a map of wilderness quality of Europe does well at picking out the mountainous areas, at least in the central and southern states (see Figure 2).

Rural depopulation, the industrial revolution, changing fortunes and patterns of agriculture, new service economies and a shifting demographic have all combined over the years to create an upland moorland landscape in Britain today, that while generally regarded as relatively wild from a perceptual stand point, is ecologically impoverished. Overgrazing by sheep, cattle and deer has prevented regeneration of the natural woodland cover that was originally cleared for agriculture, timber and fuel. There are precious few, ecologically-intact uplands left and fewer still natural tree lines remaining in the high mountains of Britain. All have been altered by human controlled grazing and/or artificially high numbers of grazing animals. In addition, muirburn and other moorland management practices including drainage and persecution of predator species also maintain most upland landscapes in ecological limbo as well as generating downstream impacts such as in-channel sedimentation, elevated DOC levels and flooding. All but a few of the highest mountain areas have been directly modified in some way, either now or in the past, and even these are subject to climate change and impacts from recreation. Some species have undoubtedly benefited from human activities and these are now used, for better or worse, as an excuse for maintenance of the status quo under the current regime of habitat and biodiversity action plans.

Figure 1. Comparison between wildland quality and altitude

Further more, upland landscapes are often the most favoured areas for renewable energy development, especially wind and hydro power, creating a conflict between a desire to preserve landscape quality and the need to be seen to doing something about reducing carbon emissions from power generation. While touted as ecologically benign, wind and hydro power do have adverse impacts on sensitive upland environments including disruption of carbon stores in peat lands, river regimes and wildlife all the while creating the afore mentioned visual impacts.

The wildness of our upland landscapes is one that is largely reinforced by perceptions of remoteness, absence of modern human artefacts, low population density and land use that is largely extensive in nature and dominated by traditional agriculture, plantation forestry and sporting estates. They are, in the main, cultural, rather than ecological landscapes, where tourism and recreation is often the main source of income. The demand for outdoor recreation is largely met by our national parks and areas of outstanding natural beauty, many of which are in upland areas. Mountaineers, walkers, skiers, canoeists, mountain bikers, bird watchers, photographers all value our upland landscapes as places in which to practice their sport and engage with nature. In Norway they call it Friluftsliv, which literally means 'open air living' the opportunities for which could be further enhanced and made more accessible to more people in the UK.

Figure 2. Wildness in Europe

This all paints a rather depressing picture of the ecological state of our uplands, but there are areas and examples of where natural processes dominate such as the Beinn Eighe Nature Reserve in northwest Scotland. Like other natural or near-natural landscapes in lowland areas, the uplands are an important source of ecosystem services. These range from clean water supply, flood prevention, pollution sinks, wildlife habitats and recreational environments and there is a strong argument to suggest that these may be maintained and enhanced by "rewilding" carefully chosen parts of our upland landscapes. Upland rewilding projects include the work of the RSPB in Geltsdale, the National Trust, United Utilities and Forestry Commission in Ennerdale and the National Trust in Alport Valley. Many of these projects start with management plans aimed at re-instating natural processes and vegetation patterns such as re-wetting of floodplains, re-establishing riparian vegetation, removing non-native species, and reducing grazing pressure and promoting naturalistic grazing by large herbivores to encourage more natural vegetation patterns and mosaics. Some include the removal of human infrastructure such as deer fencing and 4WD tracks.

However we look up to them, our uplands are a wildland resource that is worth protecting and promoting. As Price puts it, they are the "antithesis" of the city and as such as good a place as any to start when looking for wildness in our countryside and as cores from which to create a more connected landscape that will benefit both wildlife and people.