What's in a language

[ << ]

Most languages work the same way and have the same bits you can use to solve problems. Below are outlines of these bits plus examples from Scratch and Python.

It is worth noting that all that was needed to write the programs that landed people on the moon was the first four: variables; operators; branching; and loops. The rest came later.

|

1) Variables: these work like "x" in algebra. They are made up of a label/name and a value this label/name is attached to. Whenever we use the name, we get the value. They are used to give a program flexibility and for storing the answers to maths and other questions. For example, your program might ask a user their name and store it in a variable so that the program can later produce personalised messages like "I'm sorry, Dave, I'm afraid I can't do that" without having to have "Dave" written into your code everywhere. If we'd written "Dave" into our code – what we call "hardwiring" – it would be useless for anyone else; much better for the program to ask them their name when they start it and store the name for later use. Once you have a variable set up, you can use its name and get whatever is associated with it. So, for example, we could do:

and the computer would print "Hello World" to the screen. Note that it doesn't matter to the computer what the name is, but we usually call it something sensible so we know what it is. In the case above "text" would be better than "x", whereas for numbers "x" might be better. Here's setting up a variable with a value in Scratch and Python: | ||

Scratch: |

Python:text = "Hello World" |

|

|

2) Operators: these change or compare variables. So, for example, when variables are numbers, you can do maths on them with "+" "-" etc. or compare them with < (less than) or > (greater than). As "=" in most languages makes a variable equal some value, to check whether two things are equal, you often use "==" (one exception is Scratch, which uses "=" for both; see below). | ||

| x = 2 + 2 |

|

|

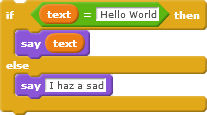

3) Branching: this lets you say "if something is true, do one thing, else do something different. |

||

|

|

|

|

4) Loops: this lets you repeat something a number of times. |

||

|

|

|

|

5) Events: code triggered when something happens. |

||

|

|

|

|

6) Procedures: little bits of code someone else has written you can reuse, for example, code to get today's date. Their code is hidden away inside a single name that you can use to run it. This is called "calling" a procedure. You can also write your own.

In the examples below, |

||

|

|

|

|

7) Objects: variables attached to code rather than words or numbers. In the examples below, "sprite1" is a load of code all bundled up together, including its own variables and procedures, so you can have variables inside other variables. |

||

|

|

|

|

8) Libraries: collections of variables, objects and procedures written by other people that you can draw into your code ("import" or "link") to do complicated jobs. Libraires save you having to write massive amounts of code: you just write the code to hold together and run the code you get from libraries. Libraries are sometimes called "packages", "modules", "dlls" in different languages. |

||

| Scratch doesn't have libraries |

In Python, the |

|

With these eight basic things, and their related code, you can build pretty much every program in existence. You put them together to make instructions or "statements" about what the computer should do, and put these together to make a program.

We'll now have a quick look at how we'd use these components to build a program.